In the world of architecture, concrete is one of the crucial materials. Currently, it is used in a wide range of projects and buildings, granting architects freedom in creating beautiful designs. Its potential seems almost inexhaustible and continual innovations in how it’s applied make it valuable to new architecture concepts.

What is concrete?

Concrete consists of cement, water and a stone aggregate. The producing process is as follows: cement, a hydraulic-setting binding agent, produces a cement paste when mixed with water, which is then enriched with a stone aggregate. The paste envelopes the small pieces of stone, fills the hollows and makes the wet concrete workable, until it hardens through hydration. The concrete then stays rigid, even under water and has a stable volume.

Brief history

The next big thing is reinforced concrete, which has led to a revolution in architecture. Steel possesses a high tensile strength, unlike concrete, and therefore makes large spans possible, without the need of arching. Its image as a cold and inhuman material was particularly prevalent in the 1970s.

Great examples

Architecture

Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, France / Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, France, is one of the most significant Brutalist buildings in the world. The architect intended for the slab-style tower, built in 1952, to house those displaced in World War II, and many of the original residents still live here. Today the complex has 337 apartments, two shopping galleries, a hotel, and a rooftop art program.

The Cidade das Artes in Rio de Janeiro / Pritzker Prize

From the top terrace of the Cidade das Artes in Rio de Janeiro, you can see both the mountains and the sea. The curvilinear concrete walls, an homage to Brazilian modernist architecture of the mid-20th century, create an interplay between voluminous shape and empty space, visible from a distance.

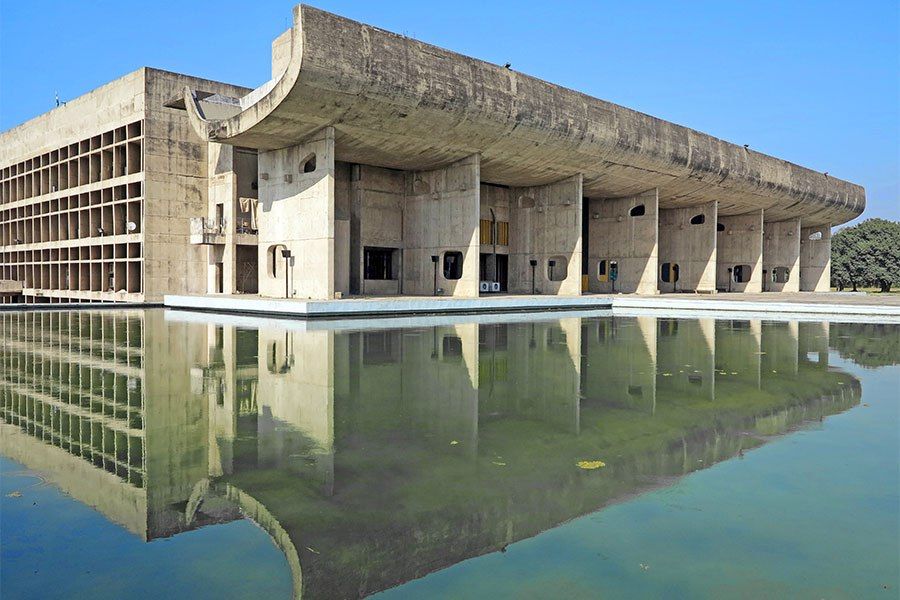

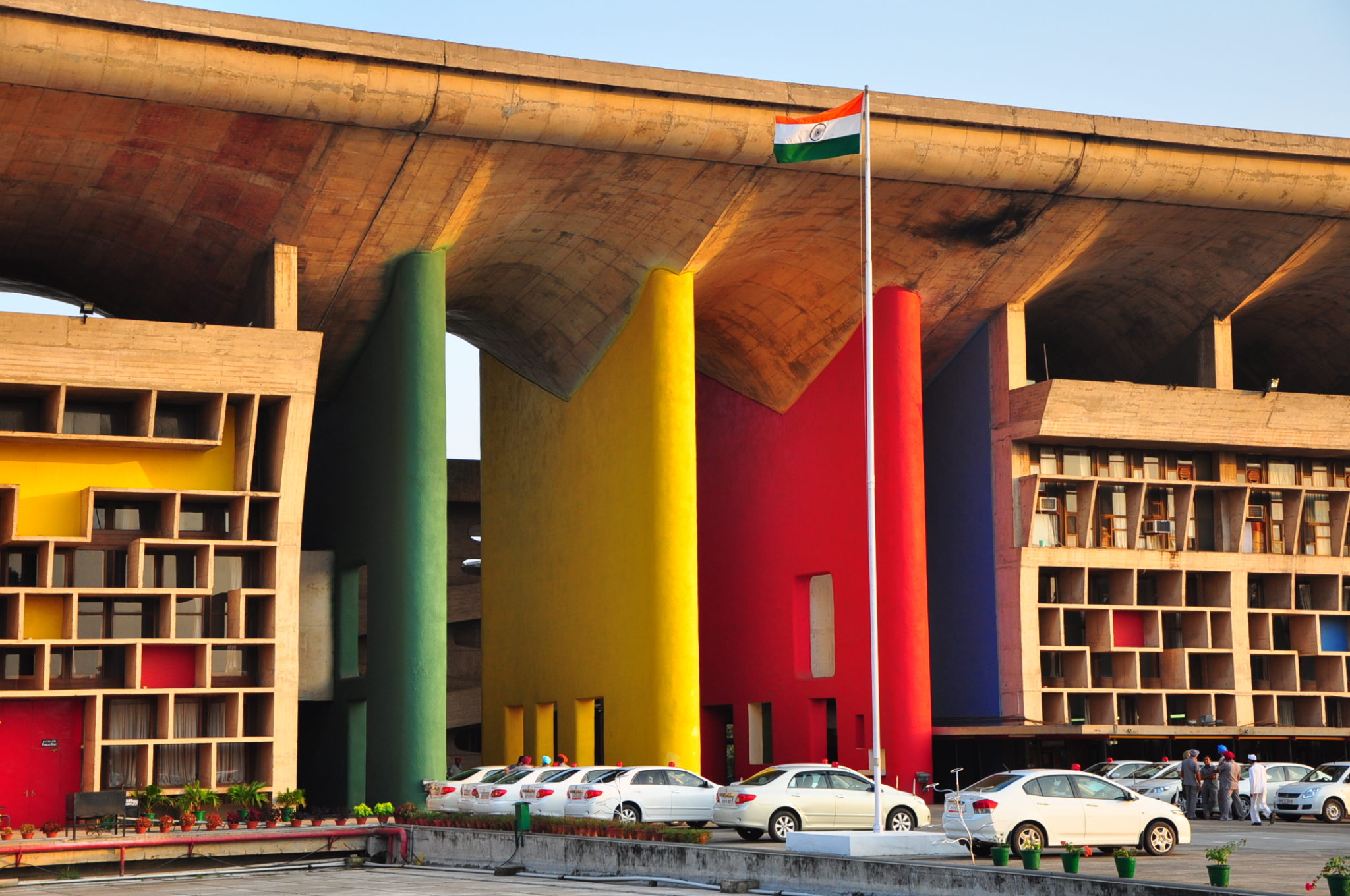

Chandigarh designed / Le Corbusier with Pierre Jeanneret in post-independence India

Chandigarh was built largely out of concrete. In the Palais de l’Assemblée, situated on a reflecting pool, the swooping sculptural form at the entrance contrasts with the building’s linear concrete columns throughout.

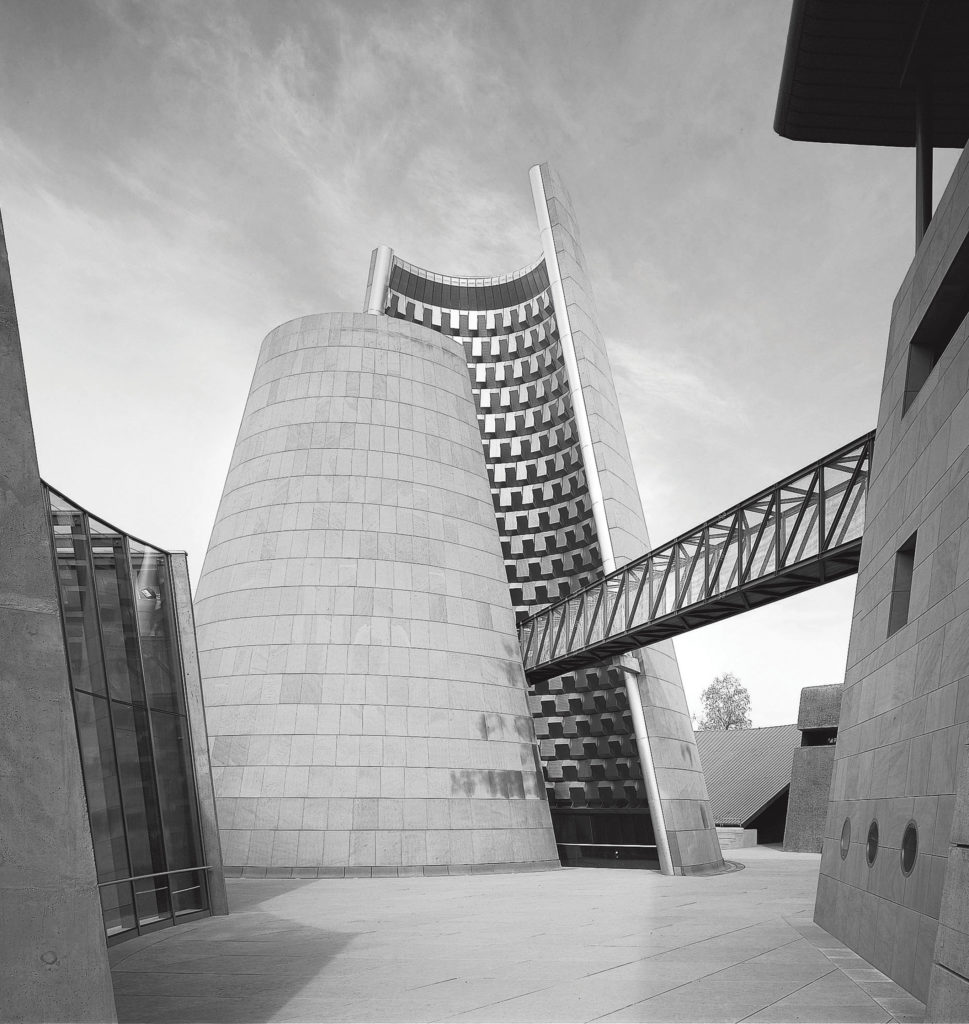

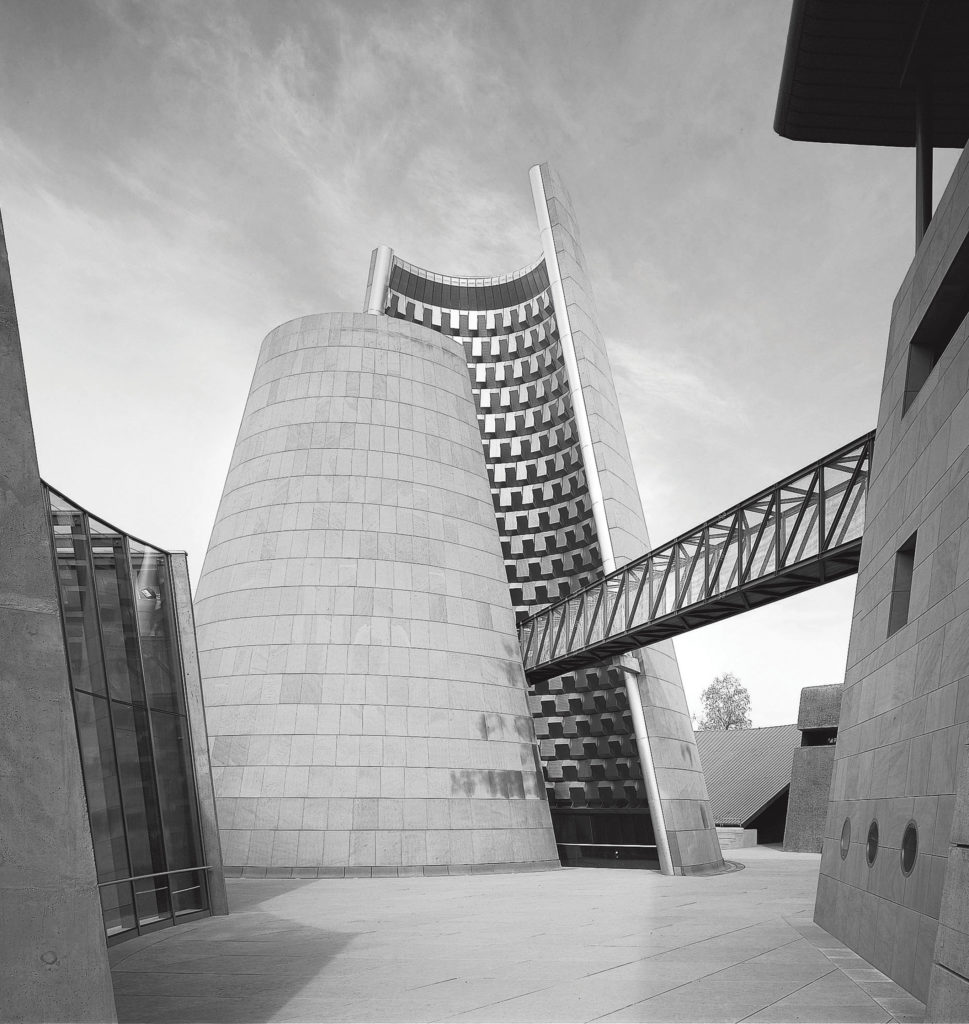

Ayla Golf Academy & Clubhouse in Aqaba, Jordan / Oppenheim Architecture

Miami-based Oppenheim Architecture has designed an incredibly cool, curvaceous clubhouse for the Greg Norman-designed Ayla golf course in the ancient city of Aqaba, Jordan, taking inspiration from the surrounding desert landscape.

Concrete waves emulate the rolling dunes and mountains of the Jordanian desert, forming an expansive shell that dictates spatial distribution. A local artist applied a traditional pigmentation technique to the interior surfaces, giving a raw and unadorned look that stays true to the desert context.

Interior Design

Concrete bunker at Sydney’s Camperdown suburb / Matt Woods

Brutalism is a perfect choice for the couple who was seeking a minimalist lifestyle, and a home where the bare essentials are enough. The architect also believed this bunker celebrated Camperdown’s industrial heritage. Geometry and clean lines help achieve a minimalist style but much care was taken to prevent them from looking too rigid.

Blue Eye in Taipei, Taiwan / Wei Yang International Design Associates

The muted tone of Blue Eye is formed by the consistent cool palette. To balance it, the architects have layered concrete in various shapes and shades so that the home does not look monotonous. They also let the living room and kitchen to be filled with natural light through the use of large windows.

88 Lounge, Viet Nam / D&P Associates

Located on the bank of West Lake – Hanoi, 88 Lounge is a wine bar & restaurant that brings you an experience like no other. Stemming from the love for wine, 88 Lounge desires to spread the wine culture from the very heart of Hanoi.